Dr. Neel Rekha

Senior Fellow, Ministry of Culture, New Delhi, India

Abstract

This paper traces the historiography of Maithil Paintings of 50 years after independence (1947 to1997) – a phase marked by its discovery, commercialisation and promotion as a fine art. The paper begins with the 1949 article of Archer published in Marg and demonstrates how many interpretations articulated by Archer formed the basis on which foundations of regional and national historiography of Maithil art were laid. Drawing attention to some recent writings who have raised questions regarding the misinterpretations, the paper demonstrates how certain important issues have been unaddressed, the two most important of them being the marginalisation of women and the absence of scholarly attempts at recording the systematic history of Maithil Painting. The paper finally draws attention to certain recent transformations in the historiography of Maithil art. The paper is a revised version of the paper titled ‘Maithil Paintings: An Enquiry Into Its Historiographical Trajectory’ presented at 61st session of the Indian History Congress Kolkata, 2001.

Full Version of The Paper

Read PDF

The phenomenal popularity of Maithil paintings in India and abroad has generated a lot of academic interest among scholars in the past few decades. Ever since Archer drew the attention of the art lovers towards this theme, it has been a hotly contested subject with scholars raising a number of issues revolving around the interpretation of the various motifs of the folk art-form. These debates have been generated largely due to the differences in approaches of scholars who have indulged in interpreting the art form dictated by their immediate objectives without meditating significantly upon the distorting interpretations of the past. This has shifted the focus on many insignificant facts leaving important issues unaddressed, the two most important of them being the marginalisation of women and the absence of scholarly attempts at recording the systematic history of Maithil Painting. This paper traces the historiography of Maithil Paintings of 50 years after independence (1947 to 1997) – a phase marked by its discovery, commercialisation and promotion as a fine art.

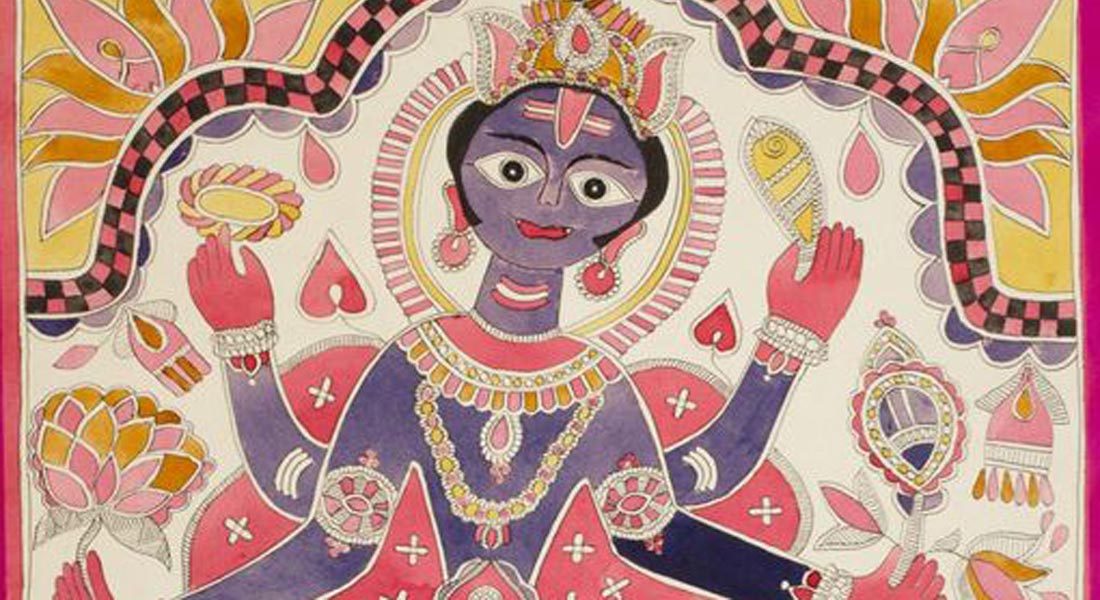

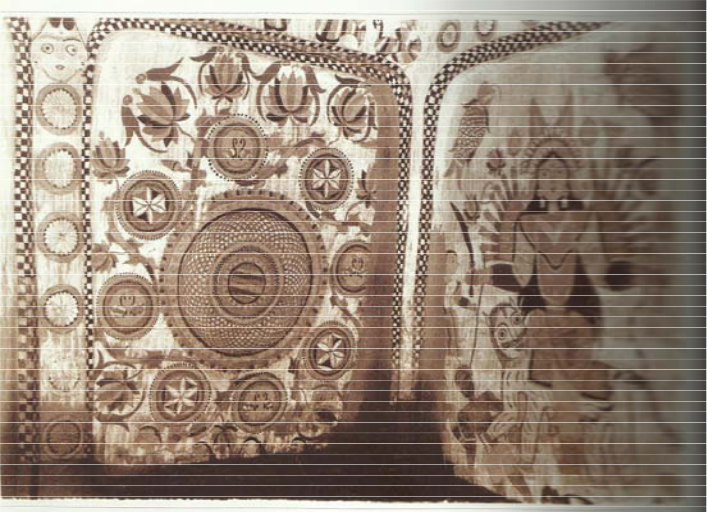

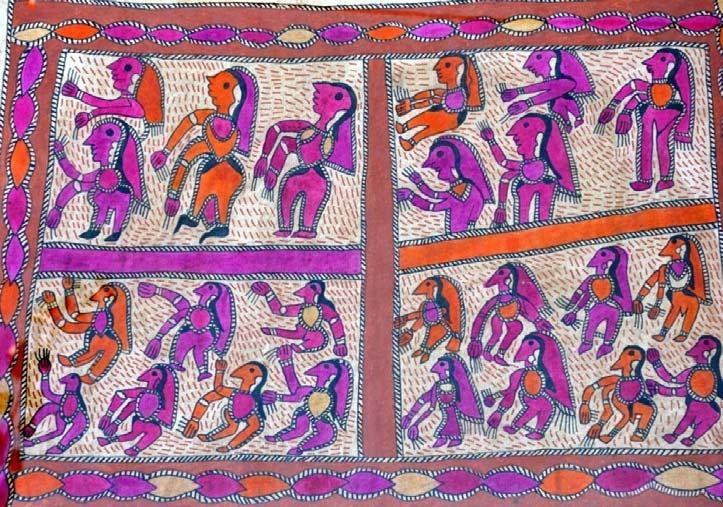

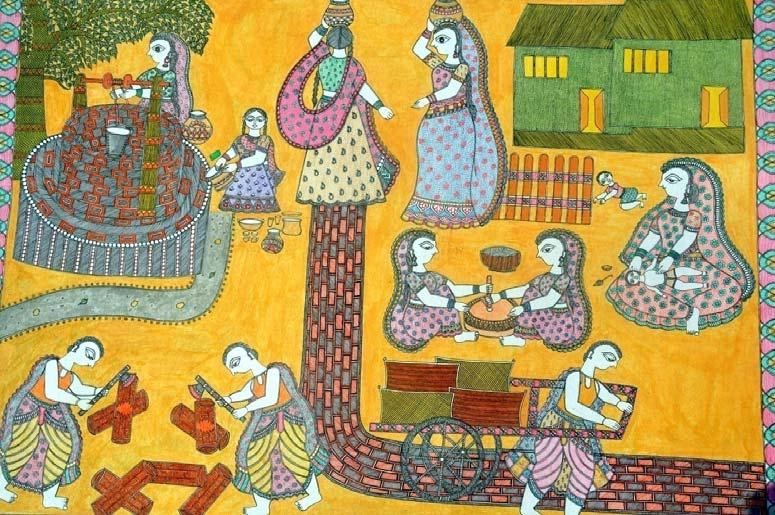

The ceremonial folk paintings of Mithila1 popularly identified as Madhubani paintings after the name of the sub -region of Bihar, have been preserved till today by the women of the region. These folk paintings, dating back to very ancient times are executed throughout the region of Mithila, constituting two very important traditions of aripanas or floor drawings and wall paintings, the most special of which are made on the occasion of marriage ceremonies. (See Figure1) It was W. G. Archer who took the earliest academic notice of this painting in the year 1934 when a disastrous earthquake broke open the murals in the Maithil households. The subsequent presentation of his researches covering almost all the areas of Mithila appeared in the Marg in 19492i which made a descriptive analysis of the art form almost divorced from its historical roots. Although he succeeded in drawing the attention of the art-lovers towards this art form, caste became his prime focus for distinguishing and explaining the various styles, besides ignoring and misinterpreting a few significant facts. This approach of Archer was shaped by two basic elements – the influence of colonial academic scholarship and his search for popular paintings.

While outlining briefly the traditions of paintings in Mithila, Archer’s analysis remained centered chiefly around the paintings of the Brahmanas and Kayasthas which he called the two caste styles. Archer’s description of the stylistic similarities and differences of Brahmana and Kayastha paintings were influenced by the colonial academic scholarship which essentialised Indians chiefly in terms of castes. His researches were based on the colonial ethnographic tradition which relied mostly on upper caste informants. The various plates provided in the article were classified as ‘Brahmin or Kayastha’ paintings. This colonial attitude of providing upper castes a disproportionately important place even in the evaluation of a folk art form, in turn, blinded him towards the cultural outputs of other communities. Significantly, he noticed them during the course of his field work. He thus wrote, “It is true that Rajputs, Sonars, Ahirs and Dusadhs also do painting and it is almost as if painting is endemic to the region. But in these latter cases the styles are more fragmentary and it is likely that the custom of painting developed later – Maithil Brahmins and Maithil Kayasths setting the fashion and isolated households of other castes following their example. In its broad essentials Maithil painting is the painting of Maithil Brahmins and of Maithil Kayasths3.” The article, itself, had a plate of a horse made by the Ahir community4. In many households, the paintings had been made by Kumaharas or potters5. Yet he not only failed to enquire upon the painting traditions of others in detail but also went on to ignore them completely thereby presenting a one-sided analysis of the painting traditions prevalent in Mithila.

This influence also got reflected both in his comparison of Maithil paintings with western counterparts and in the interpretation of Kohabar motifs6. (See Figure 1 and 2).Thus describing their paintings, he wrote, “If we are to find an analogy in European art we might say that the colours of brahmin paintings are parallel to those in paintings by Miro while those of Kayastha paintings resemble the black and terracotta colours of Greek vases7 .” To understand the significance of the Kohabar motifs painted in the bridal chamber, he drew analogies from the poems of the 17th century poet, Herrick. The interpretation of fish as emblem of fertility and Lotus and bamboo as male and female sex organs were also the influence of Herrick8.

Another factor influencing his research and perception of Maithil paintings was his obsession to discover, collect and preserve some of the best specimen of Maithil paintings. This period saw renewal of interest in primitive arts which were viewed as precursors of modern art. Added to this was growing interest among Indians as part of the new nationalist discourse. The nationalist movement’s emphasis on the portrayal of India’s rich cultural past attained a positive expression in an effort by scholars and administrators to revive the folk arts of India most explicitly manifested in Gurusaday Dutt’s9 search for the folk arts of Bengal. Influenced by these contemporary developments, Archer too became interested in searching popular paintings in the provinces of Bihar and Orissa where he got posted after joining the civil service. With the exception of Diwali Paintings10, he could not find any interesting examples of popular paintings till 1934 when a disastrous earthquake exposed the brilliant wall murals before him.

Archer’s vision being limited by his search for popular paintings, he failed to realise the implications of looking at the motifs from the perspective of men. For most of his enquiries, he consulted men for interpretations11. Depending on the interpretations provided by men in an area which had been the exclusive preserve of women resulted in a series of wrong observations besides his indifference towards some significant facts. Thus he totally neglected the floor drawings or aripanas in his discussion although he collected their specimens in the form of photographs and paper patterns or aide-memoirs12. The pictures of Naina Jogins 13 which he took away in large numbers were mistaken as veiled brides (See Figure 3). Although he mentioned the significance of the lotus and bamboo as symbols of fertility, he went on to add his own interpretations of the two symbols as male and female sex organs. It also appears to be more likely that his interpretation might have been endorsed by the men of the households where he conducted his surveys14.

Reflecting the same colonial perspective, Mildred Archer’s treatment of the subject is extremely significant for filling the void between the two significant phases in the history of Maithil paintings – the first academic notice in 1934 and the rediscovery of the art form in 1966-6715. An earlier article by her in the year 1966 in the Marg, reflected the same perspective summarising in short W. G. Archer’s research on Maithil paintings16 . Since Archer never worked on Maithil paintings after the publication of his article, his interest having shifted to other areas such as Kalighat and Pahari paintings, her first hand original information on the researches of Archer are helpful in reconstructing many facts in the historiography of Maithil paintings, most important being the account of Archer’s discovery of Maithil murals, the areas covered by him and some valuable insights into the contemporary Maithil society. Being witness to the earlier style, her brief account of the changes in style and imagery authenticated by a collection of pictures of the 1930’s and 1940’s as well as those belonging to the post-commercialisation phase, are extremely significant for determining elements of change and continuity in Maithil paintings. She writes, “These paintings differ from earlier examples in that their size is considerably larger and there is a far wider range of topics and imagery17.”

A major departure from the colonial tradition was reflected in the writings of a group of Maithil scholars, whose primary concern lay not in examining seriously the art form but to project the rich cultural heritage of Mithila. Aiming chiefly at portraying the various regional customs, the traditions and the historical background, their writings too were marked by total absence of emphasis on locating the historical roots or at analyzing the worldview of women through the paintings. Their writings also marked the beginnings of the obsessive influence of Archer which was further elaborated in the works of later scholars.

Reflecting explicitly the regional sentiments was Lakshminath Jha whose book18, though chronologically located next to Archer, presents a totally different perspective. With the aid of illustrations, almost all the kinds of painting traditions related to festivals and marriages were explained. The most significant aspect of his book was the fine portrayal of different aripanas, not explained in any of the later works and the added description of little known customs and traditions of Mithila. The pictorial compilation and the references that accompanied each picture aimed at providing readymade reference to the later scholars. Despite the originality of the book, his background as an artist committed him more towards providing a comprehensive account of the pictorial traditions than providing an analysis of the historical roots of the art form. The description of the rich cultural pattern in the 1960’s was also suggestive of the prevalence of the art form contrary to the impression gathered by Pupul Jayakar19 about its extinction when she found faint traces of paintings on her visit to Mithila in the mid 1950’s20.

This regional perspective is further reflected in Upendra Thakur’s treatment of the art form21. He provided not only an elaborate account of the aripanas and wall paintings but also gave a detailed description of its style and background taking into account almost all the researches till date except Vequaud’s. His deep understanding of the region as a Maithil and a historian of Mithila got reflected not only in his references to the brief history of Mithila but also to the literary sources of the region. Despite his efforts, he failed to break the narrow bounds of caste centered colonial perceptions of Archer and described the paintings in terms of Brahmana and Kayastha styles. This interpretation of the art form in terms of caste styles in turn led to the strengthening of the roots of the colonial perceptions in the historiography of Maithil paintings. But an analysis into the motives behind Thakur’s colonial hang-over reveals that his prime concern was not a deep rooted study but the compilation of a comprehensive account of the Maithil paintings with a view to project the rich cultural heritage of Mithila.

V. Mishra’s treatment of the cultural history of Mithila22 was refreshingly original without showing any trace of western influences or regional inclinations. Although aimed at presenting a cultural history, it devoted almost equal attention towards tracing the political developments. Though not focused entirely on the art form, the discussion on aripana was especially relevant for the insightful approach towards the subject. Whiletrying to locate various references of aripana in the texts of Mithila, Mishra attempted to trace its antiquity to Brahma Purana23. The examples from various Tantric works were cited to prove the Tantric influence on the paintings. This is helpful in locating the origins of paintings in the context of the emerging regional formation. Citing evidences from Vidyapati’s works such as Padavali24, he concluded that in the 14th century A.D., aripana had developed in all it details in Mithila. A significant aspect was the discussion on the contribution of women to philosophy and literature but even here the gender bias got reflected in the centrality accorded to male scholars as against the marginal space accorded to female scholars like Viswas Devi 25. Despite the lack of any direct treatment of Maithil paintings, the depth of information provided on religion, philosophy, literature and social life helps a great deal not only in locating the history of Maithil paintings but also in examining and analyzing its various facets.

Distinguished from the regional scholars were a group of non-Maithil scholars like J.C. Mathur, Pupul Jayakar and Mulkraj Anand who sought to introduce some significant changes in the existing paradigms through their writings. Although adopting a non -partisan approach towards the paintings and attempting to provide fresh analytical and paradigmatical inputs, the fact that they drew heavily from the colonial as well as regional writers, conditioned and patterned their interpretations of the paintings.

The perception of Lakshminath Jha got expression through J. C.Mathur26 who remained firmly rooted in his regional milieu. Besides providing an analytical account of the folk paintings based on Jha’s researches, he also elaborated upon certain important issues totally ignored by Archer, i.e its historical location. Making an attempt to trace the roots of this art form, he wrote, “The origin of this continuity may be traced to the continuous spell of Hindu rule in Mithila from 1097 A.D. to c. 1550 A.D under the Karnatas and the Oinavaras which continued uninterruptedly under the Khandavala dynasty (Darbhanga Raj) till the present day.” 27 His deep insight into the paintings notwithstanding, his extreme dependence on Lakshminath Jha’s researches got reflected in some of the superficial inferences. Denying the connectivity between the artistic traditions of upper castes women and those of the lower classes, he also went on to elaborate a distinctively women’s folk art form as a Kulin home art. He thus wrote, “The Kulina art of Mithila has refinement, continuity and a literary base which one cannot expect in the tribal art or in the folk- art of the village people,” 28 His excessive stress on the conservatism of society is a further result of Jha’s influence. He writes, “This relationship between the home-arts and the conservatism of society presents an interesting sociological phenomenon which, if studied minutely, will reveal certain significant facets of this ancient culture hitherto unknown29.” By laying excessive emphasis on conservatism, he was trying to negate the changes that might have been taking place in the style of paintings through the centuries.

Largely instrumental in making the paintings popular outside Mithila, Pupul Jayakar30 inaugurated an era of fresh serious and sustained effort in the historiography of Maithil paintings, providing centrality to women in her writings marginalized till then by the narrow approaches of the earlier writers. As the Chairperson of the Handicraft Handloom Corporation of India, Jayakar helped the Maithil women artists by providing official patronage and encouragement as part of the relief programme during the Bihar Famine of 1966. Her articles written at different stages of the commercialisation process not only reflect a balanced approach towards the interpretation of the various styles but

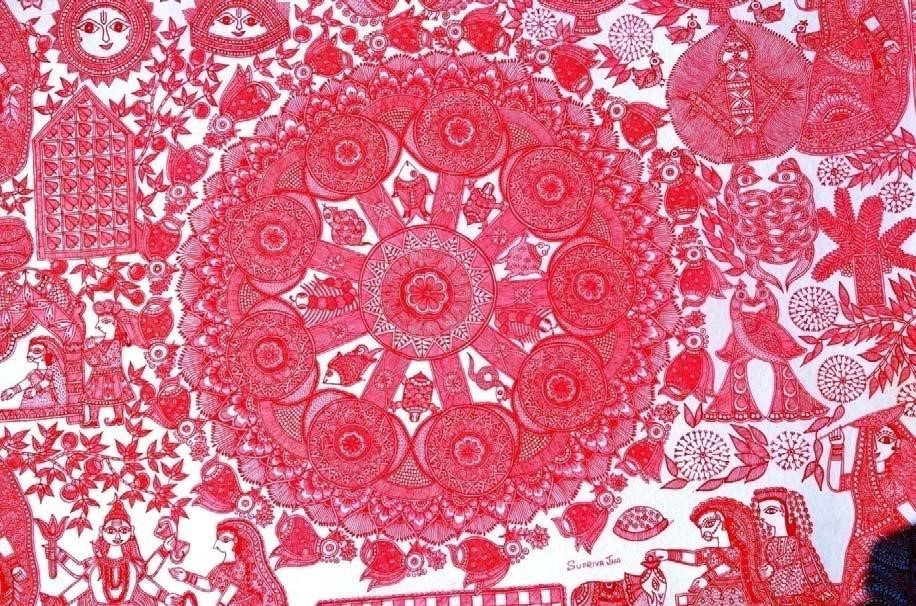

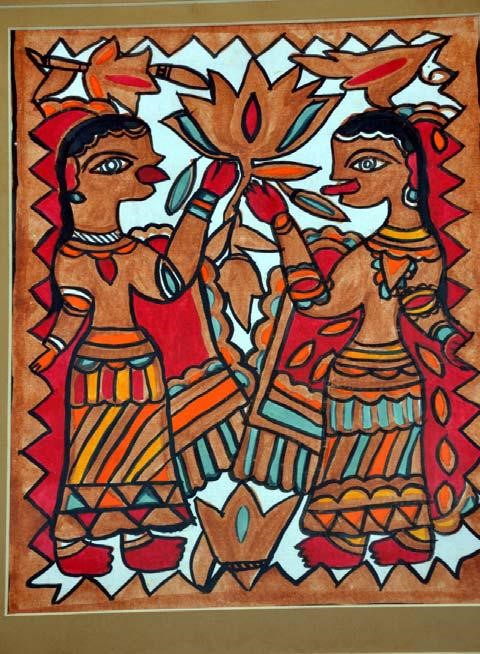

are also suggestive of the growing feeling of self worth of the women of Mithila. Further, the chronology of the articles are helpful in locating the evolution of various styles of paintings at different periods of time. Equally refreshing is her attempt at correcting the colonial paradigms constructed by Archer and followed by many later writers. Instead of categorising this folk art tradition on the basis of castes, the differences in the stylistic techniques and colour were used by her as the determinants in explaining and classifying the various types of paintings prevalent during that period. Of special significance is the reference to the Geru style of painting31 in view of the total extinction of this style in the present times and absence of references in any other literary source32. (See Figure 4).

The importance accorded to women’s rituals and aripanas in her writings, frequent references to the gradual evolution of prominent artists like Sita Devi, Jagdamba Devi, Bhagvati Devi belonging to different schools of paintings mark the beginnings of a new phase of making women the prime focus in the historiography of Maithil paintings – a trend which gradually attains maturity in later writings. For her the different paintings were individual works of the women artists recognizable by their distinguished style and characterized by their attempts at using different types of vertical and horizontal arrangements to indicate different incidents separated by time and space. Despite the fresh insights provided by her, she too failed to come out of the influence of the extant colonial paradigm in her interpretations of lotus and bamboo as male and female sex organs33.

Mulkraj Anand’s book34 explores the mythological influences on the sources of the folk art of Madhubani ignoring all the earlier writings on the subject. The most significant aspect of his book is the unique collection of very old paintings dating to the period when the paintings had just gained recognition. Thus we have very good references of line and colour paintings as well as Harijan paintings35, (See Figure 5) for tracing the elements of change and continuity in the painting style. Supplementing Jayakar’s analysis of the extinct painting style are some of the pictures of Geru paintings.

The arrival of westerners in Mithila initiated a new phase in its historiography, for a culture totally isolated from external influences was now being interpreted from alien paradigms, the most interesting example being presented by Vequaud. Of the various foreigners coming to Mithila, the most prominent were Yves Vequaud, Erika Moser, Raymond Lee Owens and Tokyo Hasegawa36 Although all of them contributed in their own way towards the revival and popularization of the folk art form, the most significant academic contribution came from Vequaud whose work resulted in the worldwide popularity of Maithil Paintings. The significant distortions of facts made by him regarding Maithil society depict the problems of interpretation in ethnographic studies and the interpretations of symbols using alien hermeneutics.

The wrong constructions of facts about an alien society by a foreigner responding to a western audience, found eloquent expression in the writings of Yves Vequaud37 Many of his descriptions about Maithil society stand nowhere close to reality even in the remotest sense, despite the rich cultural experiences derived from his prolonged stay for two years. Thus a society which had always been patriarchal was observed as matriarchal and the gathering of young men at Saurath Sabha38 was taken as a symbolic representation of the freedom of choice where girls came to select boys for marriage. He

thus wrote,” Mithila’s is a matriarchal society, and there are regular gatherings of young men to which girls who want to marry come39.” The girls then produce ‘marriage proposal drawings, called Kohabars, and present them to a boy of their choice. Elaborating upon Archer’s description of lotus and bamboo as sex organs, he went to add Tantric influence on the paintings. For him, the pictures were “heavily charged with Tantric symbolism” and exemplified their “artists knowledge of the symbolism and arcana of Tantrism40 .” One needs to understand the rationale behind such interpretations. Being an outsider, a journalist and film maker, he was not only unable to appreciate the nuances of most of the customs and traditions of the Maithil society but also could not attempt a serious academic study of the paintings. The result was wrong interpretations bordering on complete distortion of factual statements. He wrote, “There is no question of male or female dominance, but Life itself is venerated ; so that the simplest and most intimate ceremony in which a man and a woman may participate is both cause and effect of the Kohbar which is unique in the history of the world’s glorious art – a glorious crucifixionseen on the walls of every bedroom in Mithila41.”

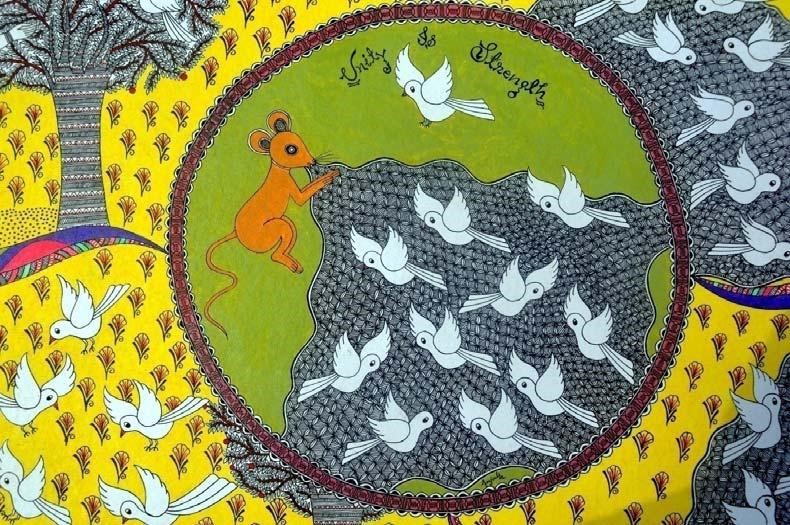

A significant shift in the historiographical trends has been articulated in the analytically sophisticated writings of some recent scholars whose focus on women have led them to project the subsequent expressions of individuality by the artists through their art form and analyse the extant paradigms through a thorough examination of the previous distortions by the earlier scholars – an area hitherto unexplored by the previous writers. This shift was clearly visible in Jain’s42 analysis of the life and works of Ganga Devi- a fine line drawing artist. Focusing his article around Ganga Devi, Jain has tried to deny the excessive stress laid on conservatism by scholars regarding folk art forms and their subsequent projection as ethnographic samples created to perform magical or ritualistic functions. This perceptual position has in turn led them to deny not only the role of external influences in changing the style of the art forms, but also to over-emphasize their negative impact .But the most important aspect is the emphasis laid by Jain on the creative individual expression of Ganga Devi through her paintings. Citing the various examples from the works of Ganga Devi, Jain has analyzed the excellent use of tradition and individual expression by a folk artist responding to the changed circumstances of her life. Ganga Devi’s exposure of a totally different world had a positive impact on her evolution as an artist. The different series of paintings made by her such as the Cycle of Life, Ramayana series, American series were reflections of the growth of a rural artist’s work from her early paintings to her venturing out into a new narrative and autobiographical work, and the invention of a new pictorial vocabulary. These were executed brilliantly by a creative use of the old stylistic devices of Maithil paintings to portray new experiences of the contemporary environment, most explicitly manifested in her depiction of a roller coaster ride in America43.

Jain’s new insights notwithstanding, his vision got limited by Ganga Devi’s perceptions of Brahmana and Kayastha styles. She being his chief informant, had the limitations of projecting the caste bias, the Kayastha point of view. He thus attributes the tradition of Kohabar painting to the Kayastha community of Mithila whereas in reality the tradition exists in almost all the communities. His perception of Kohabar painting as paintings done on paper leads him to draw this conclusion for the Kayasthas had a special practice of preserving specimens of paintings on paper many of which were also collected by Archer – a practice which was not prevalent in other communities.

The issue of the empowerment of women of Mithila was taken up by Devaki Jain44. Taking into account the lives led by them both before and after commercialization, she tries to bring out the changing social realities of their lives after their art received recognition. The incorporation of empirical details derived from field data, which also included the researches done by Raymond Lee Owens45, the detailed accounts of the awards, exhibitions, market trends, the evolution of different styles help in locating the various stages of commercialization of the art form. Citing the reports of her surveys on the impact of commercialization on women, she concluded that the ability to earn an income had clearly enhanced their status. She wrote, “They have been transformed from the ‘dependent partner’ into a vital contributor to family income. This fact alone has endowed the women with a certain distinction and esteem46.” Her arguments about the empowerment of Maithil women were supported by examples of the lives of almost all the prominent artists such as Sita Devi, Mahasundari Devi, Baua Devi, Ganga Devi and Jamuna Devi. Of special significance were the references of people closely associated with the popularisation of the art form, such as Bhaskar Kulkarni, Upendra Maharathi and H.P. Mishra47.

The exercise of analysing the previous paradigms, a practice initiated by Jain, receives full treatment by Carolyn Henning Brown. The consciously exploratory character of her articles on the art form were basically the result of her encounter with a society totally different from what was portrayed by Vequaud in the course of field work done for studying the Panji system in Mithila48 . A review of Vequaud’s work thus became the subject of her first article whose focus lay on correcting the distortions made by him, besides raising a number of significant questions. She thus wrote, “The irony is that these people, so perfectly able to speak for themselves, Mithila being famed as a center of learning even more than of art, should have been so poorly served by the text, by the ethnographic description of the prefatory comments as well as by the interpretive commentary accompanying each piece49 .” Refuting Vequaud’s description of Maithil society as matriarchal, she had written, ” The Maithil Brahmins and Kayasthas are patrilineal, their ancient lineages being documented for the past nineteen generations in extensive palm-leaf genealogical records. Nor is there any sense in which power can be said to be in the hands of women at the district, village, or caste level50” But the interest in the art form generated due to Vequaud’s interpretations led her later on to a different perceptual position. Thus referring to the women of Mithila, she described,” It is a mild irony in Mithila that the fame of women has surpassed that of the men, for Mithila art is now known throughout the world51.”

An in-depth analysis of the previous paradigms with women as the central reference point is the subject of her later work52. Although the main debate centers round the Tantric origins of the paintings, the discussions on the Tantric influence poses certain significant questions never meditated before concerning the interpretations of the art form. She tries to visualize the paintings from two perspectives – an attempt to enquire into the roots of the previous distortions by earlier writers and to locate their meaning and significance within the women’s cultural world. Analyzing in detail some misinterpretations initiated by Archer, she demonstrates the manner in which it got articulated in the later writings. To her, the debates on Tantric origins have arisen largely due to the lack of women’s participation in the meaning-making process. The Tantric origins, she feels, are the results of conversations between a few Brahmin men and a few western scholars predisposed to find Tantric meanings in the art form because of the extreme popularity of Tantra in the west. The exploration of further details leads her to establish its relationship not with Tantra, but to the reflection of the female mind in a patriarchal setup, where their role was limited to the continuity of patrilineages. The whole world of kohabar motifs representative of fertility symbols were created by women to explain their role in a patriarchal setup. Her insights notwithstanding, her complete denial of Tantric influence have to be examined in the light of various influences on the art form. The aripanas which are symbolic magical figures, the widespread prevalence of the practice of painting Naina Jogins, the use of various vernacular Tantric mantras to cure diseases and the predominance of the Shakti cult in Mithila point to the importance of Tantricism in Mithila. Yet for according importance to women in understanding a feminine art form and incorporating their viewpoint is a contribution of C.H.Brown which cannot be denied.

This paper has traced the historiography of Maithil Paintings from 1947 to 1997. The trajectory of the historiography of Maithil painting in these fifty years after independence, demonstrated a slow but gradual movement towards analytical maturity i.e. a shift from the simple colonial analysis of the caste styles to the more complex study of the motifs as reflections of the female mind. It was only towards the end of this period that scholars began to question the colonial interpretations articulated even by native scholars. While it provided the women a place they rightly deserved, many important areas still remained unexplored in this period. This phase, as remarked at the outset, was marked by the absence of attempts at historical study of paintings and marginalization of women.

As Maithil painting is a timeless artistic activity, it needed to be situated it in terms of its origins and subsequent growth, i.e. in its proper historical setting. Most of the primary sources suggested that this artistic development was a result of the regionalisation of Indian culture Documents like Panji Prabandha53 and Varnaratnakara of Jyotirishvara54 suggest that during the post-Gupta times, the culture of the region came to acquire an identity of its own. These early and medieval texts underlined the emergence of feudalism as a social formation which influenced both the material and cultural developments in the area. These primary sources also indicated that this art form came to acquire its present shape when Tantricism had permeated the social life of the Maithils. The emergence of Maithil paintings, as suggested by the primary sources, needed to be rooted in the emerging regional context, i.e in a period which coincided also with the establishment of Tantricism in the area.

The mechanism through which women created space for themselves also needed to be analyzed in greater details. The primary sources did not talk directly about this painting style. These absences in the historical texts if viewed carefully, had the potential to suggest that the patriarchal setup was not prepared to take cognizance of the major cultural constructions of the women of the region. In effect, the references to Maithil paintings could be fruitfully exploited to get an idea of the mechanism through which the women folk of the area did succeed in creating space for themselves despite patriarchal hegemony.

The mechanism of assertion of identity through religious imagery by Harijan women also remained unexplored in this phase55 Contrary to the examples in other parts of India where political recognition had elevated their status, it was art here which played an important role in providing them economic empowerment and social recognition. With the two greatly deprived groups of Maithil society making considerable impact on the society, the traditional roles assigned to these groups by a patriarchal and caste based society remained shattered. The contemporary social realities resulting due to the altered caste and gender equations in the society needed to be examined in greater detail.

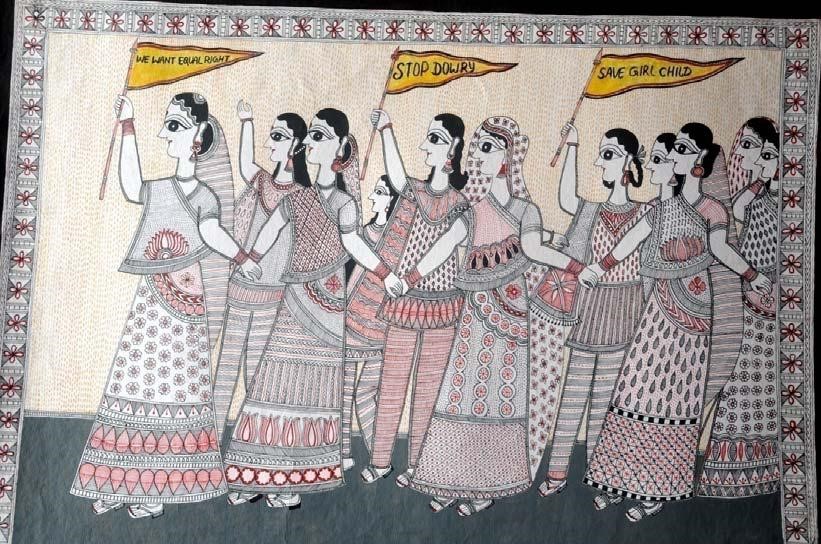

The phase after 1997 has seen growth of interest by local and international scholars in exploring the social dimensions of Maithil art. Some of the writings in this period have addressed many of the questions which remained unaddressed in the earlier phase. These include the sociological study of Maithil paintings56 , the history of evolution of Maithil Paintings and assertion of identity by women in a patriarchal society57, the evolution of Harijan Mithila paintings58, contextual study of paintings59 and its transformation and into a fine art60. However, the recent scholarly discourses on its transformation into a fine art raise further significant questions in its historiography. A number of writings by David Szanton61 and the efforts of Ethnic Arts Foundation, USA62 have drawn attention of the world towards the evolving trajectories of Maithil art63. (Figure 6 and 7)

This is bringing into light some of the new themes taken up by women painters in Mithila such as feminist paintings (Figure 8), environment paintings, current social commentary apart from innovatively using older themes such as scenes from the Ramayana and Naina Jogins64 (Figure 9). Many men have entered the field asprofessional painters. This changing face of Maithil art might open up some new paradigms in the historiography of Maithil art65. While this might add new dimensions in its historiography, it is also likely that many of the misinterpretations will still continue to be articulated, if the voices of women are not heard and contextual studies not initiated. A very recent study by Carolyn Brown Heinz has drawn attention to this66.

A number of questions still remain unanswered, the most important being the caste based distinctions. Most of the scholarship on Maithil Paintings in the past few years still categorise them in terms of caste styles. The use of different styles which emerged after commercialization could open up research into the diverse painting traditions prevalent in Mithila67. Current research suggests that upper caste women are still marginalized in the tradition. Their voices need to be heard to understand aspects of the past. A new phase of speaking up for themselves has been initiated by Harijan women painters who have used the iconography of their local gods to bring forth voices of the past68. The demands of commercialization have put great deal of pressure on women artists in Madhubani to change their age old idioms, styles, motifs and meanings. However, the articulation of new meanings distort the realities of the past and help reinforce many misinterpretations. Keeping in view the fact that the importance of visual resources is slowly being recognized as a vital source in South Asian art scholarship, it is important that these past records as expressed in Maithil women’s age old ritualistic tradition and art are preserved. Two specific examples to retrieve the voice of the past could be suggested. The Naina Jogin paintings lost from the pictorial vocabulary of Maithil women painters and now preserved in the British library, could be instrumental in understanding how women in medieval Mithila used these paintings as a medium of assertion of their identity. Many rare Geru paintings preserved in books and in the collection of museums could be another source for retrieving the history of women and the cultural interactions between women of different classes. All these extant sources of Maithil art definitely call for adopting ethnographic approaches to understanding Maithil paintings and the history of its evolution.

Acknowledgments

This paper which forms a part of the first chapter of my dissertation Art and Assertion of Identity: Women and Madhubani Paintings was presented at the 61st session of the Indian History Congress, Kolkata, 2001. I remember with gratitude the contribution of my supervisor Late Professor V. K. Thakur under whose guidance this paper was written. I have written a later version of the paper titled ‘From Folk Art to Fine Art: Changing Paradigms in the Historiography of Maithil Painting’ published in Journal of Art Historiography (2010) which incorporates in detail the later developments in the historiography of Maithil art. I also owe my gratitude to David Szanton and Parameshwar Jha, Ethnic Arts Foundation, USA in encouraging me to continue my research on the historiography of Maithil art and for allowing me to use many paintings from their collection for illustrations.

Notes

- Mithila, also known as Videha and Tirabhukti or Tirhut boasted of a very ancient origin. Presently it comprises the modern districts of Madhubani, Darbhanga, Samastipur, Vaishali, Muzaffarpur, Champaran, Monghyr, Saharsa and Purnea in the state of Bihar and about 10, 000 sq. miles in the kingdom of Nepal.

- W.G. Archer, ‘Maithil Painting’, Marg, Vol.3, No. 3, 1949 pp.24-33. On 15th Jan. 1934, a disastrous earthquake ravaged Madhubani sub-division causing extensive damages. While conducting relief operations, W.G. Archer, a British I.C. S. officer, then posted as the S. D. O. of Madhubani came across some of the brilliant murals painted on the inner rooms of the damaged houses. A serious study was started on Maithil paintings in 1937-38 when Archer was posted as the Collector of Purnea district. These studies were further conducted in 1940 when as Provincial Census Superintendent, he visited Darbhanga and Purnea Districts again. The result of these investigations were published in an article ‘Maithil Painting’ in Marg in 1949.

- Ibid. , p. 25.

- Ibid. , p. 33.

- Mildred Archer, ‘Maithil (Madhubani) Paintings’, Indian Popular Paintings in the India Office Library ,London, 1977. Mildred Archer mentions, “Discussions with the families also revealedthat in the more affluent households the women were beginning to think that the painting of walls was menial and beneath their dignity……. Some of the richer families were even employing lower caste Kumhars (potters) to execute the paintings.” p.89.

- Kohabar is an elaborate painting done on the walls of the Kohabar ghar (wedding chamber)where the newly weds spend their first four nights after the wedding ceremony. The central motif comprising mainly of Purain (lotus plant) is surrounded by different painted images: two parrots making love in the air, fish, tortoise, the sun, the moon, palanquins, grass mats, bamboo grove, and a scene of worship of Gauri.

- W. G. Archer, op. cit., p.32.

- Ibid., pp. 28-29. See also Mildred Archer, op.cit., pp.86-87.

- Gurusaday Dutt, ‘Folk Arts and Crafts Of Bengal: The Collected Papers’, Calcutta, 1990. Most of his papers on the folk arts of Bengal are compiled in this volume.

- W. G. Archer, ‘Diwali Painting’, Man In India , Vol. 24, June 1944, pp. 82-84 . These paintings were drawings of sprouting trees and human forms painted in white or red on the outer walls of village houses.

- Mildred Archer, ‘Maithil (Madhubani) Paintings’, Indian Popular Paintings in the India Office Library, London, 1977. Mildred Archer, wife of W. G. Archer has provided a first handoriginal information and background of Archer’s researches in this book. She writes, ” A number of Maithil men helped him with enquiries and arranged for him to see the bridal chambers and inner rooms of houses”, (op cit. p. 89).

- Ibid., p. 101. Reference of an aripana in white on the mud floor in the bridal chamberphotographed by W.G. Archer in 1940 on the occasion of a first marriage.

- Naina Yogins are the four veiled women painted in four corners of the Kohabar ghar inMithila and are supposed to ward off the evil eye. Archer mistook them to be brides on account of their veiled faces. Many photographs and paper drawings of Naina Yogins were taken by him and were preserved in the India Office Library, now part of the British Library.

- Mildred Archer, op.cit. She mentions about Pandit Shivnarain Das of Samaila (Darbhanga) explaining W.G. Archer about the depiction of lotus and bamboo in kohabar painting. p. 86

- Mildred Archer, op.cit., pp.85-103.

- Mildred Archer, ‘Domestic Arts of Mithila: notes on painting’, Marg, Vol.20, No.1, 1966, pp. 47-52.

- Mildred Archer, op.cit., p. 90. In 1975, Pupul Jayakar, on hearing that the India Office Library possessed a collection of early paintings, generously arranged to present the Library some paper paintings executed by the women who were sponsored by the Board.

- Lakshminath Jha, Mithila Ki Sanskritika Loka Chitrakala (Hindi), Patna, 1962.

- Pupul Jayakar was the chairperson of Handloom Handicrafts Export Corporation (HHEC) and the main force behind the commercialisation of Maithil Painting. In the late 60s, these wall and floor paintings were brought on paper as part of the relief programme started by the Government of India after the region suffered a series of droughts. The idea was to provide the drought stricken people especially women an alternative source of employment. Apart from Pupul Jayakar, Bhaskar Kulkarni, the officer in charge of the drought relief programme of Madhubani and Upendra Maharathi, an artist and designer – were the key persons responsible for the evolution of Madhubani paintings.

- Pupul Jayakar, ‘Paintings of Mithila’, The Times of India , 1971. She writes, “ I visited Mithila in the early fifties and was dismayed to find that the glory to which Archer referred had seemingly vanished. The bleak dust of poverty had sapped the will and the surplus energy needed to ornament the house. The walls were blank or oleographs and calendars hung in the gosainghars. There were only traces of old painting here and there – fragments that boretestimony to the existence of powerful streams of inherited knowledge of colour, form and iconography.’ p.29.

- Upendra Thakur, Madhubani Painting, New Delhi, 1982.

- Vijayakant Mishra,. The Cultural Heritage of Mithila, Allahabad, 1979.

- Brahma Purana is one of the important eighteen Puranas . While the first part describes thecreation of the cosmos and the deeds of Gods like Rama and Krishna, the second part describes Purushottam Tirtha, which is one of the holy places.

- The celebrated Maithil poet Vidyapati (1350- 1450) was a famous Vaishnava poet of Mithila. His works cover a whole range of subject including smriti (Vibhagsara, Ganga Vakyavali and Dana Vakyavali); on niti or moral tales (Saiva Sarvasvasara and Purusha Pariksha); on puja (Saiva Sarvasvasara and Durgabhaktitarangini) and on literary composition (Likhanavali). Vidyapati became immortal on account of his songs in Maithili, now commonly known as Padavali in which he sung praises for Radha and Krishna.

- Viswas Devi was a queen in medieval Mithila who ascended the throne after the death of her husband Padmasimha, the younger brother of Shivasimha in 1431 AD. Padmasimha died after a year of ascending the throne after which Viswas Devi took over the management of the state in her hand. She is said to have ruled Mithila for 12 years till 1453 A.D. See Upendra Thakur, History of Mithila, Darbhanga, 1956, pp.262-63.

- J. C. Mathur, ‘The Domestic Arts Of Mithila’, Marg , Vol.20, No.1, 1966, pp. 43-55.

- Ibid., p. 35.

- Ibid., p.33.

- Ibid., pp.34-35.

- Pupul Jayakar, ‘Paintings of Mithila’, The Times of India Annual, 1971, The Earthen Drum : An Introduction to the Ritual Arts of Rural India, New Delhi, 1981, The Earth Mother : Legends, Ritual Arts and Goddesses of India , San Fransisco, 1990

- A style of painting distinguished by total lack of ornamentation with more emphasis on volume and depth. Prevalent in the 1960’s and 70’s and practised by artists like Bhagvati Devi and Ookha Devi of village Jitwarpur, this style has now become totally extinct due to lack of patronage.

- This style is a good example of the cultural interactions between various classes of women. In some recent writings, it has been categorised as a Harijan style of painting.

- Pupul Jayakar ‘Paintings of Mithila’, op. cit., p. 36.

- Mulk Raj Anand, Madhubani Painting, New Delhi, 1984.

- This refers to the newly evolved Gobar and Godana styles of painting evolved by Harijan women living in the vicinity of Madhubani. The villages Jitwarpur and Laheriaganj are specially known for these paintings. Some of the important artists include Jamuna Devi, Shanti Devi and Chano Devi.

- Yves Vequaud, a French journalist and film maker was the first to arrive in Mithila in1973. Next came Erika Moser, a German anthropologist and folk-lorist whose most significant contribution lay in the evolution of Tattoo painting, besides the production of 19 short films on paintings and related subjects. Raymond Lee Owens, an American anthropologist did a 15 month cultural study of Jitwarpur and founded the Master Craftsmen’s Association of Mithila( MCAM) in 1977. The last foreigner to visit Madhubani in 1989 was Tokyo Hasegawa, a Japanese whose Mithila Museum has concentrated totally on the acquisition, display and research of Maithil paintings.

- Yves Vequaud, The Women Painters Of Mithila : Ceremonial Paintings from an Ancient Kingdom, London, 1977.

- Saurath Sabha was the oldest of the Sabha-Gachis in Mithila, where Maithil Brahmanas from all over Mithila assembled to negotiate and settle marriages after consulting all the genealogical records with the help of Ghatakas (marriage-contractors or go- betweens) and Panjikars (genealogists).

- Yves Vequaud, op. cit., p.17.

- Ibid., p.17.

- Ibid., p. 17.

- Jyotindra Jain, ‘Ganga Devi: Tradition and Expression in Mithila (Madhubani) Painting’, in Catherine B. Asher & Thomas R. Metcalf (ed.), Perceptions of South Asia’s Visual Past, New Delhi, 1994, pp.149-157 ; Ganga Devi :Tradition and Expression in Mithila Painting , Ahmedabad, 1997. In his book on Ganga Devi, Jain also throws light on the later autobiographical works of Ganga Devi such as her pilgrimage to Badrinath, the Cancer series portraying her battle with cancer in a Delhi hospital and the Japan series.

- ‘Ganga Devi: Tradition and Expression in Mithila (Madhubani) Painting’, op. cit., p.156. According to Jain, this painting in terms of space use and composition, was rooted in the traditional aripana and had been inspired by an earlier naga puja diagram made by her.

- Devaki Jain, Women’s Quest For Power: Five Indian Case Studies, Delhi, 1980.

- Ibid., pp. 193-20. The inclusion of Raymond Lee Owens’ survey conducted in 1977 issignificant in the absence of any such similar account. The book also incorporates the field work of Subodh Nath Jha which did a census of 135 households in 1977 and a third field survey of 30 households by Nalini Singh of the Institute of Social Studies in 1976.

- Ibid., p.186.

- Ibid., pp.212-17.

- Carolyn Henning Brown, ‘The Gift of a Girl: Hierarchical Exchange in North Bihar’, Ethnology, Vol. 22, 1983. pp 53-63.

- Carolyn Henning Brown, ‘Folk Art and The Art Books: Who Speaks For The Traditional Artists?’ Modern Asian Studies, Vol.16, 1982, pp. 519-522.

- Ibid., p. 520.

- Carolyn Henning Brown, ‘The Women Painters of Mithila’, in the Festival of India in the U.S., 1985-86, New York, 1985, pp. 155-56.

- Carolyn Henning Brown, ‘Contested Meanings: Tantra and the Poetics of Mithila Art’, American Ethnologist , Vol.23, No.4, 1996, pp. 717-737.

- The Panji or Chronicle locally known as Panji Prabandha of the kings of Mithila and other important people is an important document prepared in the time of Harisimhadeva, the karnata king of Mithila. It begins in Saka 1235 ( 1313 A. D. ) in the reign of Harsimhadeva ( C. 1303 – 1326 A. D.)Along with genealogies, it also enlightens us on the socio- religious condition of the people during the period. Panji Prabandha refers to the writing down of the genealogies for all the superior castes in Mithila. Genealogists began to record each family’s ancestors for six generations to avoid incest. This system became popular among the Brahmanas and Karna Kayasthas of Mithila. For more on the Panji system among Maithil Brahmanas and Kayasthas, see Ramnath Jha , ‘Maithil Brahmano ki Panji Vyavastha’ , Darbhanga, 1962.; Binod Bihari Verma, ‘Maithil Karan Kayasthak Panji Sarvekshan’, Madhubani, 1973. See also Carolyn Henning Brown, ‘Raja and Rank in North Bihar’, Modern Asian Studies, Vol.22, No.4, 1988, pp. 757-782.

- The book belongs to the 14th century A. D. and represents the golden period of the history of Mithila. It is a long prose work divided into seven chapters called ‘kallolas’. Dr. Chatterjee writes in the introduction to Varnaratnakara that is a compendium of life and culture of medieval India in general and of Mithila in particular. See Jyotirishvara, ‘Varnaratnakara’, ed. S.K. Chatterjee and B. Mishra, Calcutta, 1940; Jyotirishvara, ‘Varnaratnakara’, ed. Ananda Mishra and Govinda Jha, Patna, 1980.

- The only exception was the treatment of themes and subject matter of Harijan Paintings by Jyotindra Jain. See Jyotindra Jain, ‘The Bridge of Vermilion: Narrative Rhythm in the Dusadh Legends of Mithila’, in B.N. Goswamy and Usha Bhatia ed., Indian Painting: Essays in Honour of Karl J. Khandalvala, New Delhi, 1995, pp. 208- 209.

- Manishekhar Singh, Folk Art, Identity and Performance: A Sociological Study of Maithil Painting, Unpublished Ph.D Dissertation, Department of Sociology, University of Delhi, 1999;‘A Journey into Pictorial Space: Poetics of Frame and Field in Maithil painting’, Contributions to Indian Sociology , Vol. 34, No.3, 2000, pp. 409-442.

- Neel Rekha, Art and Assertion of Identity: Women and Madhubani Paintings, Unpublished Ph.D Dissertation, Patna University, 2004.

- Neel Rekha, ‘Harijan Paintings of Mithila’, Marg, Vol.54, No. 3, 2003, pp. 64-77.

- Carolyn Brown Heinz, ‘Documenting the Image in Mithila Art ’, Visual Anthropology Review, Vol.22, No.2, pp.5-33, 2006.

- David Szanton is a social anthropologist interested in researching the evolving trajectories of Maithil Painting. He has been following the evolution of Maithil artists and Maithil painting, since 1977. A co-founder of the Ethnic Arts Foundation started by Raymond Lee Owens in 1980, he has been involved in numerous exhibitions and other projects aimed at gaining appreciation for the painting tradition, as well as art- and life-sustaining income for the Maithil painters in rural Bihar.

- David L. Szanton, ‘Folk Art No Longer : The Tansformations of Mithila Painting’, Biblio, March – April, 2004; David L. Szanton and Malini Bakshi, Mithila Painting : The Evolution of An Art Form, California, 2007.

- The Ethnic Arts Foundation is a non-profit organisation founded in 1980 dedicated to the continuing development of Mithila Painting. The EAF supports several different activities. It purchases paintings directly from scores of painters, then organizes or co-sponsors exhibitions and sales to individuals, collectors, and museums. Profits from sales are then returned to the artists, in effect providing a double payment for their work. The exhibitions also works for expanding national and international appreciation of the painting tradition by promoting research and publications. In January 2003 the EAF established a free Mithila Art Institute in Madhubani to further the training and opportunities of talented young Maithil painters.

- The Ethnic Arts Foundation organised a large retrospective and contemporary exhibition, “Mithila Painting: The Evolution of an Art Form,” at the India Habitat Centre in New Delhi in January 2007. The exhibition included reproductions of 25 photographs taken by Archer along with 160 contemporary paintings in all the different Maithil styles by some 60 different artists.

- David Szanton and Malini Bakshi, op.cit, pp.60 -77.

- Neel Rekha, ‘From Folk Art to Fine Art : Changing Paradigms in the Historiography of Maithil Painting’, Journal of Art Historiography, Vol. 2, 2010.

- Carolyn Brown Heinz, op. cit.

- Following Archer, most of the scholarship has categorized Maithil painting in terms of Brahmana and Kayastha styles. My research suggests that at least six styles were popular after commercialisation – Bharni, Kachni, Geru, Gobar , Godana and Tantric. An exhibition titled, “ Traditional Images in Mithila Paintings” showcased all the styles in Kolkata, 2005. For more on this see Suhrid Shankar Chattopadhya, ‘Mithila’s Pride’, Frontline, Feb.11, 2005, pp. 65-72.

- Neel Rekha, ‘Salhesa Iconography In Madhubani paintings : A Case of Harijan Assertion’, BASAS Conference, Birkbeck College, London, 2006.

Folklore and Folkloristics; Vol. 4, No. 2. (December 2011)

Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Sk. Makbul Islam

View PDF

Courtesy: https://www.semanticscholar.org/

Original link: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Maithil-Paintings%3A-An-Enquiry-into-its-Trajectory-Rekha/5e623e805e68841bf851b19efedeb2e27edf0d42/

Other links:

भोजपुरी अंचल (पूर्वांचल) के कोहबर चित्र का वैशिष्टय

Documenting the Image in Mithila Art

Maithil Paintings: An Enquiry into Its Historiographical Trajectory (1947 -1997)

Madhubani Painting: A Historical Context

मिथिला चित्रकला का ‘लोक’ और उसकी प्रवृत्तियां

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed within this article or in any link are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of Folkartopedia and Folkartopedia does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Folkartopedia welcomes your support, suggestions and feedback.

If you find any factual mistake, please report to us with a genuine correction. Thank you.

Tags: Carolyn Brown Heinz, Carolyn Henning Brown, David Szanton, EAF, Ganga Devi, Godna painting, Harijan painting, J.C. Mathur, Jyotindra Jain, Maithil Painting, Mildred Archer, Mithila Art Institute, Mithila painting History, Mulk Raj Anand, Neel Rekha, Pupul Jaikar, Rani Jha, Upendra Thakur, W.G. Archer, Yves Vequaud